25 pages • 50 minutes read

Stephen CraneThe Open Boat

Fiction | Short Story | Adult | Published in 1897A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “The Open Boat”

The prolific American writer, poet, and journalist Stephen Crane is the author of “The Open Boat.” He published his short story in 1897 after surviving a shipwreck earlier in the year. To cover the brewing war between Cuba and its colonizer, Spain, Crane boarded the Commodore as 1896 turned into 1897. The ship sank, and Crane and others endured a day and a half on a tiny lifeboat. Before publishing his fictional account of the calamity, Crane published a factual article, “Stephen Crane’s Own Story,” in The New York Press.

“The Open Boat” is one of Crane’s most studied works, alongside his novella about a poor young woman, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893), and his novel about a young soldier in the American Civil War, The Red Badge of Courage (1895). The story is an example of Naturalism due to its objective and often unsentimental style. The major themes include People Versus Nature, Survival Versus Fate and Powerlessness, and Community and Cooperation Versus Alienation.

This guide refers to the 1974 version of the story included in the Washington Square Press edition of Maggie and Other Stories.

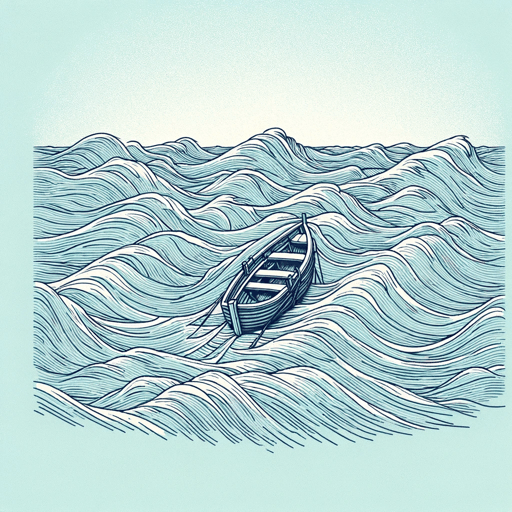

The story starts with a small boat bouncing on the waves one afternoon. In the boat are four men: The injured captain, the oiler, the correspondent, and the cook. These are the main characters, and the omniscient third-person narrator—who knows practically everything but isn’t one of the characters—only reveals the oiler’s name, Billie.

The oiler and the other characters were in a shipwreck near the coast of Florida and are now trying to survive at sea. The captain attempts to maintain a positive atmosphere. He tells the others, “[W]e’ll get ashore all right” (216), but the men are unsure. They row the dinghy, hector a bird, and try to figure out how close they are to land or rescue. The captain spots a lighthouse, but the cook informs him that the lighthouse is abandoned and has been for years.

The oiler and the correspondent row the tiny boat, and the captain implores them to row slowly to save energy. Land appears, and the cook thinks they’re near “a house of refuge” (220), but no help arrives. The captain’s positive tone turns gloomy. He says, “[I]f we don’t all get ashore, I suppose you fellows know where to send news of my finish?” (222). The question leads the narrator to thoughts about the cruelty of nature, fate, and the torment of drowning.

The waves grow stronger, but the men start to hope that someone from shore sees them. They spot an omnibus and a person with a coat, and then they notice additional people. The people are at a winter resort; they don’t help the men, and the men curse their odd and cheerful behavior.

As afternoon turns to night, the freezing waves continue to besiege the men. Now the correspondent and the oiler take turns rowing. As the correspondent rows by himself, he thinks about how he’s “the one man afloat on all the ocean” (229), even though he’s sharing a boat with three other men.

As “the dismal night” carries on (230), the narrator returns to thoughts about the cruelty of fate and drowning at sea. The narrator wonders why fate let the men survive instead of killing them immediately. The correspondent ponders a poem about a dying French soldier in Algiers. The vivid recollection makes it seem like the soldier is on the boat with the correspondent.

Without signs of rescue, morning approaches. The captain wants the men to try and make it through the surf to shore; he reasons that if they keep rowing, they’ll eventually grow too weak to save themselves. The plan sparks the correspondent to think about the relationship between people and nature. Nature isn’t evil or intelligent but “indifferent, flatly indifferent” (234).

The men prepare to face the surf, jump overboard, and swim to shore. A “tumbling, boiling flood of white water” engulfs the boat (236). After another wave besets the tiny vessel, the men go overboard. The correspondent sees the oiler swimming strongly, the cook’s back protruding out of the water, and the hurt captain holding on to the capsized boat. The captain orders the cook to turn over on his back and use the oar. Meanwhile, the correspondent swims slowly to shore. He thinks about the surreal quality of the land in front of him.

As the correspondent methodically makes his way toward land, he hears the captain calling to him for help as he clings to the boat with one hand. Exhausted, the correspondent thinks that drowning might be pleasant. While he tries to reach the captain, an extraordinary wave flings the correspondent near the land.

In shallow water, the correspondent tries to stand but realizes he’s not in a condition to do so for more than a second. A mysterious naked man with “a halo” brings the cook ashore and goes to fetch the captain, who magnanimously redirects the man to the correspondent. The correspondent is fine, but he sees the oiler lying face down on the sand, dead.

Soon, people swarm the island, and the three surviving men have all they need to recuperate. They now feel they understand the sea.

Related Titles

By Stephen Crane

A Dark Brown Dog

Stephen Crane

A Man Said to the Universe

Stephen Crane

A Mystery Of Heroism

Stephen Crane

An Episode of War

Stephen Crane

Maggie: A Girl of the Streets

Stephen Crane

The Blue Hotel

Stephen Crane

The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky

Stephen Crane

The Red Badge of Courage

Stephen Crane