35 pages • 1 hour read

Chimamanda Ngozi AdichieThe Headstrong Historian

Fiction | Short Story | Adult | Published in 2008A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “The Headstrong Historian”

“The Headstrong Historian” is a short story by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie that was first published in The New Yorker in 2008 and later as part of the anthology, The Thing Around Your Neck, in 2009. A highly decorated and award-winning author, Adichie often writes about cultural legacy, feminism, and identity, particularly as they relate to postcolonial Africa and the African diaspora—themes that echo throughout “The Headstrong Historian.”

The story centers on Nwamgba, a Nigerian woman who, after her husband’s sudden death, seeks justice against his cousins, whom she believes killed him, as well as the reinstatement of her family’s inheritance. Her efforts ultimately push her son into the hands of colonial missionaries, who threaten to disrupt and subsume Nwamgba and her family’s culture and identity. As her characters navigate their relationships within an increasing colonial power dynamic, Adichie underlines the importance of history and legacy, female resilience, and the dangers of colonial education.

This guide refers to the version of “The Headstrong Historian” in Adichie’s 2009 anthology, The Thing Around Your Neck.

The story begins as Nwamgba recalls memories of her husband, Obierika, and how they came to be married. The narrative flashes back to this point in Nwamgba’s history and then tells her story chronologically; the end of the story coincides with the end of her life.

Nwamgba’s family initially resists the marriage, as Obierika’s family is known to produce only one child each generation amid “lost pregnancies and buried babies” (199). Nwamgba is determined to marry him, though, and her father eventually accepts because he fears that she will not find a better match. Obierika’s family is not considered a bad one since his father has earned the ozo title, which marks his family’s wealth and prosperity.

When it comes time to pay Nwamgba’s bride price, Obierika is accompanied by his two maternal cousins, Okafo and Okoye. Both are envious of their richer cousin, and they often take advantage of his love for them to request goods instead of working for themselves. After they marry, Nwamgba struggles to conceive a child. Rumors circulate, and while Obierika refuses to consider having a second wife, Nwamgba decides she will find one for him herself. One day, she goes by the Oyi River to meet her friend Ayaju. A woman descended from enslaved Africans, she is shunned for her heritage but has earned respect by making trading journeys beyond the Onicha region and reporting on “the Igala and Edo traders, [and] the white-skinned men” (201). Ayaju recommends a young girl from the Okonkwo family; after another miscarriage and a cleansing consultation with Kisa, the famous oracle, Nwamgba pushes Obierika to marry her. Obierika, however, continues to delay deciding until, eventually, Nwamgba bears a son named Anikwenwa.

Anikwenwa is an industrious child who has inherited his father’s “happy curiosity.” When Okafo and Okoye come to play with him, Nwamgba doubts their goodwill and fears for her family. Obierika eventually dies under suspicious circumstances, and she is convinced they killed him. Nwamgba later regrets not requesting that the cousins drink Obierika’s mmili ozu, water that has touched the body of the deceased. According to the clan’s superstitions, if the accused drinks the water and is guilty of the crime, they will die. Nwamgba, however, is too blinded by grief, and after the funeral. Okafo and Okoye claim that titles and inheritances go to brothers and not to sons, effectively stealing Obierika’s lands, goods, and titles from Anikwenwa. Nwamgba tries to stop them; she sings in the evenings of their wickedness and asks the Women’s Council for help, which 20 of them give. Even so, the cousins continue to take what does not belong to them.

Ayaju comes back from another trading journey and has more stories about the white men. They set up a trading post and want to tell Nigerian traders like herself how to trade; they raze villages with guns; they ask parents to send their children to school, which Ayaju does. Two white men come to visit Nwamgba’s clan and identify themselves as part of the Holy Ghost Congregation. They are building a school nearby and have come to spread Christianity.

At first, Nwamgba refuses to send Anikwenwa to these missionary schools, but Ayaju tells her how the white men have a courthouse in Onicha where they judge land disputes like hers, and her perspective begins to change. Pressure mounts on Nwamgba to take another husband, and she hears stories of how missionaries saved a young boy named Iroegbunam from slave traders. She also hears how the white men’s court awarded land rights to a man who could speak their language instead of its rightful owner. Fearing that her son might be sold into slavery by Obierika’s cousins, Nwamgba finally decides that Anikwenwa should speak English well enough to go to the white men’s court instead of their own and have his inheritance reinstated.

Nwamgba visits a Catholic school to register Anikwenwa, where she meets Father Shanahan. He informs her that Anikwenwa will have to take an English name, Michael, in order to be baptized and attend classes. Nwamgba easily agrees since “his name [is] Anikwenwa as far as she [is] concerned” (208), and she sees no issue with his baptism since she believes he will only attend school until he masters the language. Though Anikwenwa does not like school and its severe corporal punishments, the admiration he receives from his peers for his clothing and his ability to speak English eventually leads him to take an enthusiastic interest in and adhere to the missionary school’s teachings on idolatry, nudity, and heathenism. He refuses to participate in his initiation ceremony and Nwamgba lashes out at him, asking whether he is her son or the priest’s. He reluctantly complies, but Nwamgba worries about her son’s views.

With Father Lutz’s help, Anikwenwa acquires papers from the court stating that the lands belong to him and Nwamgba. His father’s cousins have no choice but to return everything to him, including his father’s ivory tusk. Anikwenwa does not remain with his mother for long afterward, instead leaving for Lagos to become a teacher. For many years, he does not return home, and when he does, it is as a catechist for the congregation. According to Nwamgba, he changed so much that he is now “like a person diligently acting a bizarre pantomime” (212). When Anikwenwa decides to marry, he chooses a woman named Mgbeke, who was baptized Agnes when she was taken to the Sisters of the Holy Rosary in Onicha to learn how to be a good Christian wife. Anikwenwa refuses to follow any of their clan’s marriage rites and instead insists on a Christian ceremony that leaves Nwamgba befuddled and alienated.

Though she does not understand her daughter-in-law, Nwamgba finds that she does not hate her. When Mgbeke confides in her about her marital problems, Nwamgba “silently carve[s] designs on her pottery […] uncertain of how to handle a woman crying about things that did not deserve tears” (213). One day, the clan’s women go to the Oyi River to fetch water, but Mgbeke refuses to remove her clothes, which is against tradition. The women become outraged, beat her, and dump her into the grove. Their actions prompt a clash between Anikwenwa and the clan elders, who, though asked by both Anikwenwa and Father O’Donnell, do not apologize or compromise on their clan’s tradition. Nwamgba is ashamed of her son and his behavior but still clings to the idea of a grandchild, one who might inherit Obierika’s spirit.

A few months after a visit to the oracle, Nwamgba can tell Mgbeke is pregnant. She gives birth to a boy whom Father O’Donnell calls Peter but whom Nwamgba calls Nnamdi. She initially thinks the boy is Obierika returned but later does not feel his spirit within him. Instead, she feels his spirit in Anikwenwa and Mgbeke’s second child, a girl whom Father O’Donnell baptizes Grace but whom Nwamgba names Afamefuna, or “My Name Will Not Be Lost.”

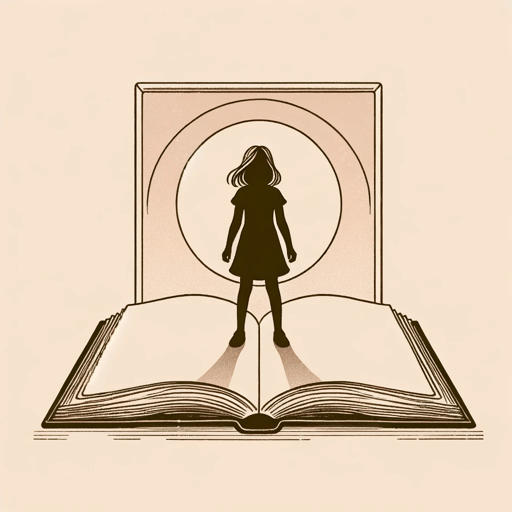

Afamefuna grows up listening to her grandmother’s poetry and stories while she works on her pottery. The year Afamefuna is sent to boarding school in Onicha, Nwamgba becomes ill and knows she will die soon. Her son pleads with her to be baptized before her death, which she adamantly refuses to do. She only asks to see Afamefuna. Anikwenwa tells her she cannot come because of her exams, but Afamefuna appears all the same because her spirit urges her home.

As she sits with her dying grandmother and holds her hand, the narrative pivots to Afamefuna’s (still called Grace) future, showcasing her struggles with her family over religion, with the education system that taught her to devalue African history, and with her career. She decides to study history after hearing about Mr. Gboyega, a Nigerian expert on British history who thought African history was an unserious subject. While she works to reclaim the history of Southern Nigeria with her research, her work is seen as indulging in “primitive culture instead of a worthwhile topic like African Alliances in the American-Soviet Tensions” (217), according to her eventual ex-husband. Amid feelings of rootlessness, she officially changes her name to the name her grandmother gave her, Afamefuna. The narrative then returns to Nwamgba, who dies holding her granddaughter with her pottery-thickened hand.

Related Titles

By Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Americanah

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Apollo

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

A Private Experience

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Birdsong

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Cell One

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Checking Out

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Dear Ijeawele, or a Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Half of a Yellow Sun

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Purple Hibiscus

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The Danger of a Single Story

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The Thing Around Your Neck

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

We Should All Be Feminists

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie