28 pages • 56 minutes read

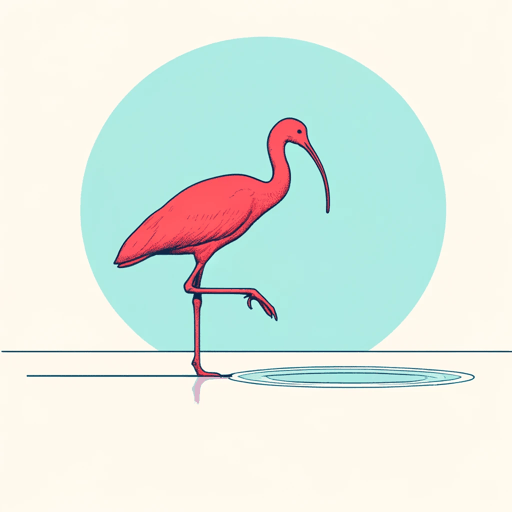

James HurstThe Scarlet Ibis

Fiction | Short Story | Adult | Published in 1960A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Summary and Study Guide

Summary: “The Scarlet Ibis”

First published in The Atlantic in 1960, James Hurst’s “The Scarlet Ibis” won the magazine’s “Atlantic First” award. Frequently included in literature anthologies, Hurst’s tragic short story explores themes of pride, shame, and death within the context of coming of age.

This guide refers to the 1960 version that appeared in The Atlantic as well as the brief biographical information included in that original publication.

Content Warning: The source text uses outdated, offensive terms to describe people with disabilities. This study guide reproduces such terms only in direct quotes of the source material.

The story begins with the unnamed narrator recalling a moment in the past between summer and autumn when a scarlet ibis landed in a bleeding tree. The narrator’s thoughts bring back the scents, sights, and sounds of the previous days and cause him to remember his younger brother, whom he nicknamed “Doodle.” The story takes place between 1911 and 1918 in rural North Carolina, during which time World War I occurred.

Born when the narrator is six, Doodle has “a tiny body which was red and shriveled like an old man’s” (48). Mama and Daddy believe the sickly infant will die, and only Aunt Nicey has hope for the boy. Daddy orders the construction of a small coffin, but Doodle survives. After three months, the parents finally name him William Armstrong.

The narrator, an active boy, laments Doodle’s inability to run and explore the world. Doctors believe that Doodle “was not all there” (49), has a weak heart, and will probably lie on a rubber mat in the front bedroom for his entire life. Dismayed by this knowledge, the narrator decides to suffocate his little brother but stops when Doodle smiles at him, which the narrator takes as a sign of Doodle’s intelligence.

Although experiencing physical obstacles, Doodle learns to crawl and talk. The narrator dubs him “Doodle” because the little boy’s backward crawling reminds him of a doodlebug. The narrator rationalizes the nickname as a kindness because “nobody expects much from someone called Doodle” (49).

As Doodle does not walk, Daddy builds a go-cart and tasks the narrator with pulling his brother around the surrounding town and swamp. While the narrator considers Doodle a burden due to his fragility, the younger brother shows an appreciation for and sensitivity to the beauty of the natural world. The brothers spend their days at Old Woman Swamp gathering flowers and weaving them into ornaments. One day, admitting that inside he possesses “a knot of cruelty borne by the streams of love” (49), the narrator shows Doodle his coffin and forces him to touch it. Doodle, frightened of the casket, begs his brother not to leave him.

When Doodle reaches five years of age, the narrator, ashamed of his brother’s disability, decides to teach Doodle to walk. For the entire summer, the narrator aids his brother in standing and then walking, viewing Doodle’s potential success as a source of personal pride. On Doodle’s sixth birthday, the brothers show Doodle’s newfound ability to their ecstatic family. When Doodle reveals that his older brother taught him to stand and walk, the narrator bursts into tears, realizing that his good deed was due to his shame at “having a crippled brother” (50) and not for Doodle’s benefit.

After the discovery of Doodle’s walking, the go-cart is put away in the barn loft with the coffin. The narrator and Doodle continue to explore their world and consider their future. Doodle, a compelling storyteller, devises tales of people with wings and imagines that when he and the narrator are grown up, they will live beside the stream and marry their parents. The narrator, while admitting the unrealistic aspects of Doodle’s plan, admires Doodle’s stories, which he calls “beautiful and serene” (51).

Not content with training Doodle to walk, the narrator decides to teach his brother other skills: swimming, tree climbing, fighting, and running. Although events in the larger world—including the Great War, blighted crops, and a hurricane—become household topics of conversation, the narrator continually focuses on his plan to make Doodle like other boys. Yet, after a year of training, Doodle makes little headway.

One day before the start of school, the family hears “a strange croaking noise” (52) coming from the bleeding tree in their yard. The bird perched in the tree, a scarlet ibis, appears worn out and ill and eventually falls to the ground dead. Its death, however, does not spoil its grace and beauty. While the rest of the family members go back to their lunch, Doodle digs a grave for the bird and performs a solemn ceremony.

Later that day, the narrator and Doodle row out into the marsh. Despite a gathering storm, the narrator forces Doodle to row back against the current. The younger brother becomes exhausted and collapses when they reach the shore. The narrator, disheartened by Doodle’s failure to acquire the skills that would make him a physically active boy, runs home in the rain, leaving Doodle behind. Doodle calls out to him, begging the narrator not to leave him.

Eventually, the narrator decides to return to Doodle, but it is too late. He finds Doodle “bleeding from the mouth […] his neck and the front of his shirt a brilliant red” (53). In realizing that Doodle is dead, the narrator begins to cry and holds the body of his brother, protecting his “fallen scarlet ibis” (53) from the storm.