65 pages • 2 hours read

Daniel Walker HoweWhat Hath God Wrought

Nonfiction | Book | Adult | Published in 2007A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Summary and Study Guide

Overview

What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 by American historian Daniel Walker Howe, explores the changes the United States underwent in the early 19th century. Awarded the Pulitzer Prize for History, the book was published in 2007 as part of The Oxford History of the United States. Howe’s work explores the political, military, social, economic, and cultural developments that shaped the nation. Howe does not shy away from the complexities and contradictions of this era, including those surrounding slavery and Indigenous relations. Prominent themes include The Political and Social Challenges of Territorial Expansion, The Rise of Religious and Social Movements, and The Evolving Debate and Conflict over Slavery.

Content warning: The guide contains detailed discussions of slavery, racism, and the displacement of Indigenous peoples present in the source text.

This guide refers to the 2007 Oxford University Press edition.

Summary

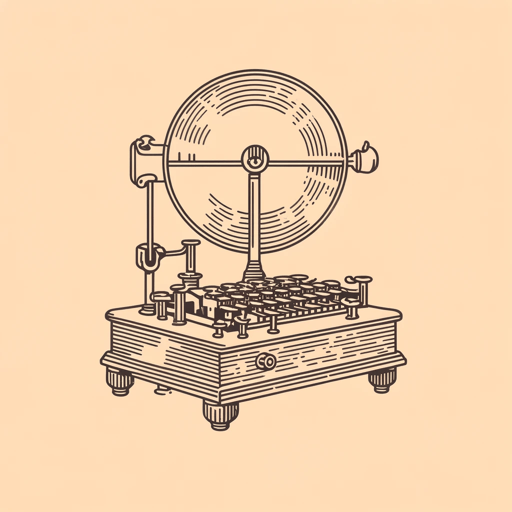

What Hath God Wrought offers a nonfiction narrative of the United States from the end of the War of 1812 to the conclusion of the Mexican-American War in 1848, encapsulating a transformative period in American history. The title, drawing from the first telegraphic message sent by Samuel F. B. Morse, symbolizes the technological advancements and the broader transformations reshaping the country. Howe’s narrative delves into the emergence of a communications revolution, paralleling and possibly exceeding the significance of the modern “information highway,” highlighting the impact of advances in telegraphy, printing, and transportation on American society.

The introduction of the telegraph epitomized the spirit of American innovation, closely intertwined with the idea of Manifest Destiny that propelled the nation’s expansion across the continent. This period witnessed the dramatic extension of US sovereignty, facilitated by technological advancements that not only revolutionized communication but also underscored the complex interplay between technological progress and national ambition. The narrative underscores how the telegraph and other innovations symbolized a new era of national unity and economic expansion, reflecting a broader cultural shift towards embracing technological progress as a component of American identity.

The Prologue, focusing on the Battle of New Orleans, sets the stage for the book’s exploration of the era’s military conflicts and their implications for national development. Howe underscores the critical role of artillery over the romanticized frontier riflemen, challenging the mythos of American individualism against the backdrop of emerging industrial and technological advancements. Chapters 1 through 20, along with the finale, chronicle the vast array of events, ideas, and figures shaping the period of 1812-1848. The Monroe presidency’s “Era of Good Feelings,” for instance, highlights an illusion of national consensus that masks deep-seated regional and political divisions. While symbolizing a temporary lull in partisan strife, this era also sets the stage for emerging disagreements over economic policies, territorial expansion, and the institution of slavery, such as the Missouri Compromise, portraying the complex interplay between national unity and sectional interests.

Simultaneously, the flourishing of American literature, arts, and intellectual thought during the “American Renaissance” signifies a growing confidence in American cultural identity. Figures like Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman are presented not just as literary giants but as architects of American thought, reflecting the optimism, anxieties, and ideals of a nation grappling with its place in the world. This cultural reawakening, intertwined with religious revivals and educational reforms, underscores a society in pursuit of moral and intellectual advancement.

Central to Howe’s narrative are the heated debates over slavery that increasingly polarize the nation. Discussions surrounding the Texas Annexation and the Mexican-American War, framed in terms of territorial gain and the slavery expansion debate, highlight the dynamics between manifest destiny and the moral quandaries posed by slavery. These debates foreshadow the inevitable confrontation over unresolved issues, such as those leading to the Compromise of 1850.

Furthermore, the period’s technological advancements, particularly in transportation and communication, fundamentally transform American society. The construction of the Erie Canal and the advent of the telegraph reshape the economic landscape, enhance national cohesion, and redefine America’s engagement with information and distance. These innovations facilitate the rapid spread of ideas, goods, and people across the burgeoning nation, symbolizing the era’s spirit of progress.

The book’s final chapter considers the amalgamation of progress and conflict characterizing the era. The Seneca Falls Convention, emblematic of the growing women’s rights movement, testifies to the broader struggles for equality and justice permeating American society. While acknowledging advancements, Howe also considers the looming shadows of division and discord, suggesting a nation at a crossroads, still defining its identity and principles. What Hath God Wrought presents a period of rapid transformation where technological advancements, economic developments, and ideological battles over democracy, expansion, and slavery set the stage for the Civil War. Howe’s narrative recounts the events and figures of the era and probes the underlying themes of change, conflict, and identity that defined the period.