20 pages • 40 minutes read

Wilfred OwenDulce et Decorum est

Fiction | Poem | Adult | Published in 1920A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Summary and Study Guide

Overview

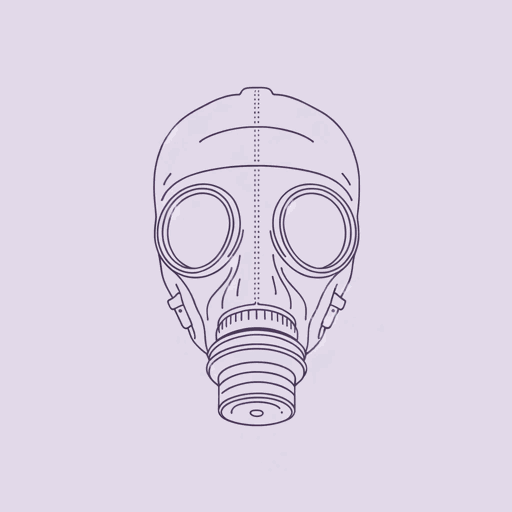

Among Wilfred Owen’s most famous poems, “Dulce et Decorum Est” was written in 1917 while he was in Craiglockhart War Hospital in Scotland, recovering from injuries sustained on the battlefield during World War I. The poem details the death of a soldier from chlorine gas told by another soldier who witnesses his gruesome end. Owen himself died in action on November 4, 1918 in France at the age of 25. He published only five poems during his lifetime. “Dulce et Decorum Est” appeared for the first time in print in the posthumous Poems (1920) and is now considered one of the greatest poems of the tumultuous period. This, and other poems of Owen’s on the topic of war, became renowned for the poet’s unflinching look at the physical horrors of warfare as well as his condemnation of those who glorified service.

The poem’s Latin title is taken from a famous line from the Roman poet Horace: “Dulce et decorum est / Pro patria mori” (Lines 27-28), which translates to “It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country.” This quote was widely used to support war efforts and as a general military philosophy in England at the time. Owen originally sarcastically dedicated the poem to his contemporary Jessie Pope, a woman poet who wrote popular pro-war poetry aimed at young men, comparing war to a game and urging them to enlist. While Owen edited out the specificity of the dedication, he did intend his poem as a response to poetry like Pope’s. The poem does not appear to be autobiographical in that Owen seems not to have experienced a chlorine gas attack in World War I. However, this doesn’t lessen his speaker’s realistic rendering of such an event nor dismisses the horrors Owen himself experienced (See: Further Reading & Resources).

Content Warning: Due to its source material, this study guide features references to and descriptions of World War I, the battle’s effects on the human body, physical descriptions of the effects of chemical warfare, and discussions of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Poet Biography

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen was born on March 18, 1893 in Oswestry, England, near the border of Wales. His parents were Susan and Thomas, a railway station master. Owen was the eldest child of four and close to his siblings and mother. He was educated at the Birkenhead Institute and at Shrewsbury Technical School. In his late teens, he began writing poetry and was accepted into the University of London but could not fund attendance. For a time, he thought he would join the clergy and worked as an assistant to a Vicar in Reading. However, this assignment also led to his questioning the church and its ability to help those in need. He went to school at Reading University College (now the University of Reading) and wrote poetry in his spare time, but he returned home in 1913 after falling ill.

Eight months later, to support himself, he worked as a private tutor of English in Bordeaux, France where he fell in love with France and befriended the elderly poet and pacificist, Laurent Tailhade, who encouraged his work. In June, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo and World War I began. Owen considered joining the French army but eventually returned to England. He enlisted in October of 1915. In the summer 1916, he became a second lieutenant in the Manchester Regiment and in December, he wound up back in France, but this time on the battlefield.

In the winter and spring of 1917, he was concussed by a shell, nearly froze to death in a field of snow, was caught in a blast that killed most of his fellow officers, saw friends and comrades die, and was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (known at the time as “shell shock”). In June, Owen was admitted to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh to recuperate. There, he edited the hospital’s journal, The Hydra, under his doctor’s encouragement. The poet Siegfried Sassoon arrived at the hospital shortly thereafter, and the two men became close friends and influenced each other’s work. Already a published poet, Sassoon encouraged, read, and edited Owen’s poetry.

Owen and Sassoon were both interested in psychoanalysis, which was new at the time, and sought to translate their emotional experiences, dreams, and dreamlike visions into poetry while interweaving stark realities of violence and war. In November 1918, Owen was discharged from Craiglockhart and began light duties in North Yorkshire. In March, he was stationed in Ripon Army Camp at its Command Depot. There, he wrote the majority of the poems that would make up the posthumous Poems. Sassoon introduced him to several important literary figures in London and in May, a publishing company expressed interest in his poetry manuscript.

That July, he went back to active duty. Owen grew increasingly distressed by wartime propaganda but felt it his duty to record the horrific realities of war. Sassoon did not want him to go and Owen kept his service a secret until he was in France. He returned to the front lines of battle a month later.

On November 4, 1918, Wilfred Owen was killed in action just a week before the signing of the Armistice that ended the war. Upon posthumous publication of Owen’s Poems (1920), edited by Sassoon, he was quickly lauded as among the best war poets of the nation. Critics believed at the time, and still do today, that his poems’ gritty realism and sympathetic tone served as an important counterpoint to the popular patriotic view of military service as an objectified, glorious endeavor.

Poem Text

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Owen, Wilfred. “Dulce et Decorum Est.” 1921. Poetry Foundation.

Summary

The poem begins with a detailed look at a group of weary soldiers, the speaker among them, as they end a day’s battle. Injured and weighed down by their equipment, they slog their way to where they will make camp. The first stanza details their physicality and centers on their extreme exhaustion, which makes them less alert to the signs of war behind them.

In the second stanza, they are surprised by a chemical gas attack and hurry to put on their gas masks. One soldier cannot secure his in time and is exposed to the burning chemicals. His comrades watch helplessly as he suffocates, as if he were drowning in water. His desperate fight for breath haunts the speaker who later sees the soldier's death “[i]n all [his] dreams” (Line 15).

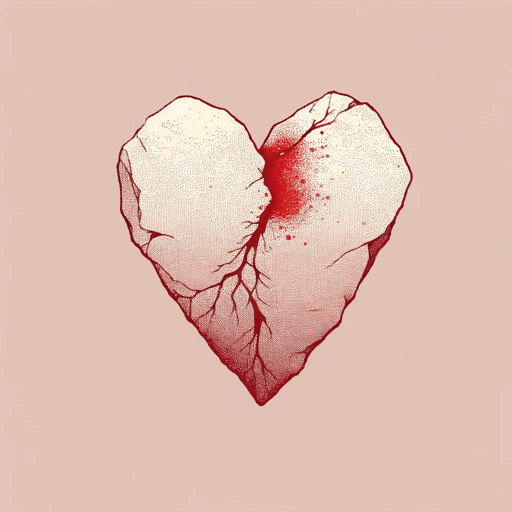

The last stanza is a passionate condemnation of those who promote war as glorious. The speaker believes if they could have seen the soldier’s slow, painful death as he was carried away in a cart, they would reconsider their philosophy. The speaker details the soldier’s blindness, his slack expression, his coughing up of blood due to his affected lungs, and the chemical burns on his tongue. He notes that if people could see these catastrophic injuries, they wouldn’t be so quick to believe—or encourage—“[t]he old Lie” (Line 27) that dying for one’s country is a grand gesture worth any price.

Related Titles

By Wilfred Owen