41 pages • 1 hour read

Natalie Zemon DavisThe Return of Martin Guerre

Nonfiction | Book | Adult | Published in 1983A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Summary and Study Guide

Overview

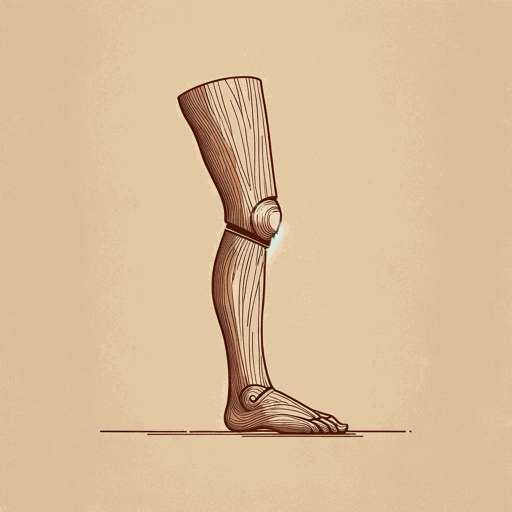

In The Return of Martin Guerre, Natalie Zemon Davis, historian and professor at Princeton University, reconstructs the sixteenth century legend of Martin Guerre, a man with a wooden leg who arrived to a courthouse in Toulouse just in time to denounce an imposter who had stolen his wife, his family, and his inheritance. Arnaud du Tilh, a clever and persuasive peasant with a somewhat sordid past, had indeed taken Martin’s identity, and he nearly escaped prosecution but for the perfect timing of the real Martin Guerre’s return home. Though this story is widely considered a legend, the characters involved were real people who lived in the Languedoc region of France during the sixteenth century. Davis blends rigorous historical research with her own informed dramatization of the events leading up the return of Martin Guerre in this book, a work of literature that defies easy classification.

Three French peasants hold the leading roles in this legendary story: Martin Guerre, his wife Bertrande de Rols, and Arnaud du Tilh, the imposter who took advantage of Martin’s absence to usurp Martin’s position. In 1527, Sanxi Daguerre, Martin Guerre’s father, moved his family from their home in the Basque region to Artigat, in the Languedoc region of France. Sanxi and his family adapted to life in their new village, learning a new language and changing their surname from Daguerre to Guerre. They assimilated well enough for the young Martin to become engaged to Bertrande de Rols, the daughter of a respectable Artigat family, but not so well that Martin felt completely at ease in his new role of husband. The newlyweds needed assistance to consummate the marriage, and eight years passed before their son was born. Martin’s humiliation was public, and Davis describes Martin as unhappy and restless, as a result of both this embarrassing series of events and Martin’s generalized sense of unease. In 1548, after disgracing himself by stealing a bit of grain from his father, Martin abandoned his wife and young baby and left for Spain. Bertrande moved back into her childhood home to live with her mother, who had married Pierre Guerre, Martin’s uncle. Humiliated and trapped by the constraints of patriarchal peasant society, Bertrande waited here, neither wife nor widow, for her husband to return for approximately eight years.

In 1556, Arnaud du Tilh arrived to Artigat, calling himself Martin Guerre and reminiscing affectionately about old times he had shared with Martin’s family and friends. Bertrande and other members of Martin’s family listened to him talk about their shared experiences and memories from the years before his exit from Artigat, and they all accepted him fully. Here, Davis veers away from the recorded facts, imagining Bertrande as a woman and wife fully cognizant of the imposter; this imagining is significant because Bertrande’s unspoken decision to accept Arnaud du Tilh though she knew he was a fraud made Bertrande a brave and unexpected champion of her own cause and her own willful pursuit of happiness. This departure from the historical documents that frame the legend of Martin Guerre is one example of Davis’s unique writing style that blends creative writing with historical retelling.

Within a few years of his arrival to Artigat, Arnaud du Tilh, the new Martin, clashed with his uncle, Pierre Guerre, who was also Bertrande’s stepfather. This conflict revived Pierre Guerre’s doubts about the true identity of the new Martin, and soon, the new Martin found himself in court, fighting for his right to Bertrande, their children, and his property and inheritance. The case was complicated and long, and witnesses were split; for as many villagers who doubted the new Martin, there were just as many who believed he was indeed the real Martin. Just as the judges were about to dismiss the charges against the new Martin, the real Martin Guerre made a dramatic return and seized his old life back from the clutches of the imposter. Arnaud du Tilh eventually confessed, apologized, and died for his crime.

Few records of the sixteenth century court case exist, so Davis relies mainly on two historical documents for the facts: Arrest Memorable by Jean de Coras, a respected judge and legal scholar of the time whom the Criminal Chamber tasked with writing a record of the case, and the popular news account by Guillaume Le Sueur, in Latin, titled Admiranda historia, and in French, Histoire admirable. Davis examines each of these records in detail, presenting the reader with a thorough description of the individuals involved in the case, the society in which the case took place, and the circumstances that permitted the events that led up to the trials to happen in the first place. Throughout the book, Davis reminds the reader that she has supplemented history with speculation and invention, and this combination of fact and fiction makes this book difficult to categorize. Whether a work of non-fiction, an imaginative history, a microhistory, or a scholarly monograph, The Return of Martin Guerre tells a true story of stolen identity with flair and memorable detail.